COMMUNITY – GROWN MAINTENANCE INFRASTRUCTURE: THE STORY OF THE ZABBALIN

A Visual Essay by Marwa Shykhon

Bio

Marwa Shykhon is an International Development consultant and Architectural Designer, currently working at the multi-disciplinary design firm, Arup. Throughout her career she has been keenly engaged on community-oriented design and public realm regeneration projects in London and Cairo. She has a sustained interest in architectural research, focussing on the challenges of sustainable urban development and maintenance in Cairo.

Desert of the Real: a visual travelogue about real and fictional infrastructures around Chott-el-Djerid / شط الجريد

A Photoessay By Michel Kessler & Pierre Musy

Chott el Djerid is a salt lake stretching over more than 7,000 square kilometers in the barren desert of western Tunisia. It is so vast that it appears to reach the stars. Across this terrain, there are real and imagined infrastructures, not only for the extraction of salt and solar energy, but also for former film sets that awaken the collective unconscious of our globalized hyperreality.

As a symbol of wealth, salt has been historically a source of power struggles, shaping the recent history of the region. In salt flats, the salt water from the lake is piped over large areas so that it can evaporate through the natural action of the sun and wind. After evaporation, the remaining brine is directed to special areas called crystallisers, where the salt will settle naturally to be harvested, washed, stored and then made available to consumers once a year.

The arid desert is also home to energy production. The sun is captured, transformed, and fed into the existing infrastructures. A 10 MW solar power project built by a European company covers an area of 20 hectares and generates 16.9 GWh of electricity.

The salt lake of Chott el Djerid is an endorheic basin flooded in winter with rainwater and wastewater from the distant Atlas Mountains. The dissolved minerals form delicate shades of pink, soft greens, blues and other subtle colors. As spring turns to summer, crystalline structures are formed and the great heat of the Sahara transforms once again the shallow waterways into glittering desert.

The salt lake shares its name with a similar feature on the largest of Saturn's 62 known moons: Titan. The Djerid Lacuna basin there is similarly endorheic - the material evaporates to form a shallow lake bed. In Tunisia, the water leaves behind dissolved sodium chloride, calcium sulfate, magnesium sulfate, calcium carbonate, potassium chloride and magnesium carbonate. On the distant moon, it is the interaction of liquid methane and ethane rather than water that shapes the landscape.

Mirages form in the midday sun. Here, the intense desert heat manipulates, bends and distorts the light rays so that you actually see things that are not there. Trees and sand dunes float above the ground. The edges of mountains and buildings ripple and vibrate. Color and form merge into a dazzling dance. The physical transforms into the psychological. The heat crystallizes a new reality.

It has been suggested that in ancient Mesopotamia, or Sumer, there was a belief that the image of the sky may have corresponded to the image of the earth. This belief held that the features of the earth, including its lands, rivers, buildings, and temples, had counterparts in the stars.

It is possible that this view originates from the optical phenomenon of the Fata Morgana, which, with its melodic Italian magic word, is on everyone's lips.

Like search parties from an alien planet, the US film industry landed in the intermittently dry salt lake of Chott el Djerid towards the end of the 20th century. They came to shoot the science fiction saga Star Wars for a generation that grew up "without fairy tales". Director George Lucas took his cue from buildings of the Imaziɣen when he dreamed up alien architecture for the Star Wars series. The low and domed dwellings of the Imaziɣen became the model for the igloo-like houses of the fictional desert planet Tatooine; the home of Anakin and Luke Skywalker above which twin suns set. It is an abandoned zone where the characters of the film exist only through the imprints they leave behind.

The postmodern situation is sometimes described as one in which the hyperreal has replaced our reality. The original has disappeared and we can only access the copy of the copy.

For the film, however, not only fictional architectures were erected in the vast emptiness of the salt lake, but artificial craters were also excavated. The power of imagination shaped the natural form of the place. Space has been the subject of fantastic projections since time immemorial. Science and art, science and fiction, and reality and fiction have never been so close as in the face of outer space -that unreachable place of longing. Thus, science fiction turns out to be a realistic genre rather than a mythological one.

Although some architecture was added in post-production using Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI), here on the edge of the Sahara, all the major buildings from the films have been preserved. A village built for fiction still affects reality after the film crew has left. Its stories are transformed into a new crystal of reality.

One does not see space here so much as time, because different layers of time with different rhythms coexist simultaneously in this place. Imaziɣen make their rounds on diesel-powered quad bikes. In this way, they re-appropriate the space inspired by their cultural practices, trying to develop alternative tourism activities. A reappropriation of the reinterpretation of their own culture by North Americans.

Futuristic high-tech transmission towers turn out to be painted wooden structures, and they now function as tethering points for horses and parking for quad bikes.

Slowly, the plaster backdrops disintegrate in the glare of the sun. Strange pipes penetrate the wall; fantastic infrastructures without purpose. The retrofuturistic doors do not open.

The threshold of the desert has always been a geopolitical point of contention. It is a diffuse zone that is constantly shifting. Officially part of a territory, it eludes control. It is almost impossible to mark a line, draw a border and create an accurate map of the place. Because more and more, climate change is turning new areas into deserts.

Photo Gallery

Note

The images used in this visual essay are stills from a documentary film Desert of the Real (2022) by Michel Kessler and Pierre Musy.

Bibliography

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacres et simulation. Collection Débats (Paris, France). Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1981.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Mille Plateaux. Collection "Critique". Paris: Éditions De Minuit, 1980.

Guattari, Félix, Architettura della sparizione, Milano: Mimesis Edizioni, 2013.

Žižek, Slavoj. Welcome to the Desert of the Real!: Five Essays on September 11 and Related Dates. London; New York: Verso, 2002.

Bio

Michel Kessler is an architect with a focus on real space. He founded his architecture practice Michel Kessler+ in 2022. Under Architecture Liminale. He assembles his paraarchitectural works between code, sound and film.

Pierre Musy is an architect and filmmaker. He is fascinated by the impact and alteration of fiction in everyday life. He also seeks to design spaces through the unconstructed by social relations.

Beekeepers' Library

A Photoessay By Joy Amina Garnett

“The Beekeepers’ Library” aims to shine light on a fleeting moment in Egypt’s modern history, a moment that nevertheless held great promise for change evinced by the cultural flowering across disciplines. It takes the form of an artistic reflection on one man’s forgotten project and the ripple effect it may have generated within and beyond his immediate circle. That man is my late maternal grandfather, Egyptian romantic poet and beekeeper, Dr. Ahmed Zaky Abushâdy (1892-1955).[1]

My aim is not to assess the success or failure of Abushâdy’s project, but to celebrate his struggle to realize it. The archival source materials at my disposal are varied, hybrid, and far ranging like their progenitor. My choice of collage as a way of parsing and highlighting speaks to the source materials’ dual attributes of malleability and resilience. Through juxtapositions of photographs, design elements, and texts, I hope the collages will at least enjoin a resonance, however oblique and amorphous, with the social, political, and environmental realities of the period from which they emerge. My greater hope is they might prompt a desire to delve deeper into this material, which has been organized as an archive and made accessible through the auspices of NYU Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) Library.[2]

A polymath who worked across disciplines, Abushâdy is remembered for his Romantic poetry and as the man behind the influential journal of Arabic poetry Apollo (Cairo: 1932–4). In the period that stretched between the two world wars and the Egyptian revolutions of 1919 and 1952, Abushâdy cultivated his vision for a modern Egypt by enacting his ideals of liberal humanism through poetry, bee husbandry, and other projects that invited cultural exchange. “Bee culture”—the notion of the “hive mind” and harmony through cooperation—was how Abushâdy broadly characterized the complex societal and behavioral patterns of bees, their systems of communication, feeding, mating, breeding, incubating, flight, swarming, dancing, temperature regulation, pollination, selection, gender-morphing, and the production of near-magical nutritional substances such as honey and royal jelly. I am not sure why Abushâdy first became interested in bees, but it may have stemmed from his research in bacteriology and infectious diseases; bee culture seems to have inspired him and provided a potent metaphor for his work.

“The Beekeepers’ Library” derives its name from Abushâdy’s eponymous flow-chart (Figure 1) and the initiatives he launched in Benson, a small village in the countryside near Oxford, over a century ago. A sketch on lined notebook paper, the chart reveals the thinking around his unrealized plan to build a lending library of books that would cover aspects of bee culture across disciplines: literature and poetry; the culinary arts; medicinal uses of pollen and royal jelly; botanical plantings for bee gardens; epidemiology of bee diseases; aerodynamics of bee flight; and standardized practices for modern beekeeping.

The collages that comprise “The Beekeepers’ Library” reflect Abushâdy’s bee culture through visual materials and texts: They incorporate photographs of his apiary in Khorshed, a village in the Nile Delta, and images of his patented honeycombs. They introduce him and his English wife, my grandmother-to-be, Annie (née Bamford), through their portraits. The collages insert elements of illustration, advertisements, and graphic design from Abushâdy’s bee journals, and are accompanied by short excerpts of the editorial he wrote for the inaugural 1919 issue of his English language bee journal, The Bee World. These excerpts are reproduced exactly as they appear, typographical quirks and all.

The year 1919 was an eventful one. As revolution raged at home in Egypt and the influenza epidemic decimated the lives of millions globally, Abushâdy established the Apis Club, a cooperative apiary with educational and research programs, in Benson. He did so with the help of investment from the Egyptian cotton magnate ‘Ali al-Manzalawi. With this financial infusion, Abushâdy launched a parent company called Adminson, Ltd. to finance the Apis Club until it could self-sustain through the annual contributions of its members. In its first year, the coop attracted over thirteen thousand members and grew to over six hundred hives, an auspicious beginning for Abushâdy’s lifelong beekeeping venture. The same year, he launched his first scientific journal, The Bee World, which is still published today as Bee World by the International Bee Research Association (IBRA), and obtained a number of British patents for beehive improvements. The most radical of these was a removable aluminum honeycomb, an upgrade of the existing removable comb whereby beekeepers can extract honey without destroying the colony, a method that remains standard practice today. Abushâdy later adapted these and other practices for use in Egyptian apiaries, where the traditional skep made from twisted straw or wicker baskets and mud was still prevalent.

The Apis Club and The Bee World journal provided Abushâdy with a platform by which he could promote his deeply felt humanist ideals. As a physician who provided care in the most basic sense, he had a vision. He’d practiced medicine during the influenza pandemic, managed cholera outbreaks, treated children suffering from malnutrition, and witnessed the effects of extreme poverty across England and Scotland. The Apis Club offered a way for him to disseminate his views and also put them into practice. He envisaged his headquarters in Benson as an educational center for experts and amateur beekeepers alike, where he encouraged knowledge sharing among beekeepers from different social strata. He used The Bee World to promote best practices so farmers could dramatically increase honey yields and improve their standard of living. He conceived the cooperative as a social and material alternative, and hands-on strategy to counter the classist, racialized, and gendered cultures that he resisted as a doctor, scientist, poet, liberal humanist, and self-proclaimed feminist.

Abushâdy met Annie, his wife-to-be, on a London bus soon after he arrived in London in 1912. She was born in the town of Stalybridge in Greater Manchester, one of twelve children from a family of pub owners, Odd Fellows, and cotton weavers. As a teenager, she read the Last Letters from Egypt by Lady Duff Gordon and the novels of D. H. Lawrence. She was a few years Abushâdy’s senior, had a head of voluminous hair upon which she perched large feathered hats, and chain-smoked. They moved into a little brick house on Cairn Avenue in Ealing, where he opened a private practice and a small research laboratory. In the backyard, they established a small colony of bees. They married before they left England for Egypt in the fall of 1922.

I often wonder to what degree Annie must have influenced Abushâdy’s ideas about cooperatives and social change. I like to think that she inspired him to implement the principles of the cooperative movement. The movement was also emerging in Egypt in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but it is reasonable to imagine that Abushâdy became enamored of the concept of cooperation through Annie and the sense of radicalism, historical depth, and proximity her family’s past conferred. She grew up not far from its birthplace in Rochdale, where the Society of Equitable Pioneers established the first cooperative nearly twenty years earlier in 1844. Also persuasive, Annie claimed Samuel Bamford (1788–1872), the famous labor organizer and voice for peaceful activism, as her forebear, although itis not clear to me how they are related. Bamford, who wrote poetry in Lancashire dialect, was present at the 1819 Peterloo Massacre and authored several books, including Passages in the Life of a Radical, a chronicle of conditions among the working classes in the years after the Battle of Waterloo.

After Abushâdy returned to Cairo, he briefly continued to edit The Bee World but soon resigned to focus his energies closer to home. In 1930, he launched a second scientific journal, The Bee Kingdom (Mamlakat al-naḥl), which accepted contributions in Arabic and English, and took in articles as well as advertizing from around the world. He established the Bee Kingdom League, an Egyptian bee husbandry cooperative, in the Matareya suburb of Cairo where he and Annie were raising their family. Under its auspices, Abushâdy published papers and monographs on aspects of bee botany, diseases, and breeding methods. With support from the Egyptian Ministry of Education, he taught beekeeping to grammar school and high school students. The Ministry of Agriculture sponsored his organization of the first international bee conference and honey fair in Cairo, and at the request of King Fu’ad, he established the Royal Apiaries. The Bee Kingdom remained in print for a decade, while members of the Bee Kingdom League continued to hold meetings and conferences long after his death, as recently as 1978.

Looking back at these collages and the materials from which they are drawn, I am left with questions. Do forgotten works of social good leave an indelible mark on communities despite their short-term failure? Did Abushâdy’s initiatives, many of which were unrealized or cut short by circumstance, nevertheless project themselves forward through time, remaining dormant to bloom at a more auspicious moment? If that were the case, was he likewise acting as the instrument of his creative and spiritual forebears? Does husbandry—for bees as well as other kinds of mentorship and shepherding—have a lasting effect in what may otherwise appear as a landscape of attrition, profound loss, and resounding darkness? I do not have the answers to these questions, nor do I expect to find them. But I am prepared to be continuously, even pleasantly, surprised by the infinite ways radical methods of hope, creativity, and community organization can blossom across time and space.

Notes

[1] The author has kept the outdated transliteration of her grandfather’s surname that he favored, which includes the Ottoman circumflex: Abushâdy.

[2] The materials from which these collages are drawn span the years of Abushâdy’s youth, his English education and marriage, his return to Egypt where he became a significant figure in modern Arabic poetry and bee husbandry, and his final years in the United States (1946–55) writing theatre and cultural broadcasts for the Voice of America’s new Arabic radio program. They include manuscripts, deeds, family trees, snapshots, large format photographs, significant artworks such as paintings, sketches, cartoons and calligraphy by artists in Abushâdy’s circle, books and serials, audio recordings, small objects and ephemera, and a large amount of correspondence in English and Arabic between Abushâdy, his peers and family members. In April 2020, New York University’s Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) Library acquired the archive and the collection is now available in the Archives and Special Collections department of the Library.

Bio

Joy Amina Garnett is an artist and writer in Los Angeles who explores forgotten histories through archival materials. Her artwork has been exhibited at the Whitney Museum, MoMA-PS1, the FLAG Art Foundation (all in NY); the Milwaukee Art Museum; Museum of Contemporary Craft Portland; and the National Academy of Sciences (Washington, DC). Her writing has appeared in a number of journals and books including Evergreen Review (New York); Rusted Radishes (American University in Beirut); Full Blede (Los Angeles); Ibraaz (Kamal Lazaar Foundation); The Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook (powerHouse Books 2016); and Cultural Entanglement in the Pre-Independence Arab World (I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury 2020). She is currently completing a memoir of Egypt.

Erasure and disembodiment as blackout: The case of Heliopolis, Cairo

A Photoessay By Amira Elwakil

الشارع دا أوله بساتين وآخره حيطة سد

ليا فيه قصة غرام ماحكيتش عنها لأي حد

من طرف واحد وكنت سعيد اوي

بس حراس الشوارع حطوا للحدوتة حد

This street has gardens at its entrance and a walled dead end

In it I have a love story that I have told no one about

A one-sided story, but I was still elated

Now the street guards have put an end to it

- The Streets are Stories, poem by Salah Jaheen, sung by Al-Massrieen

The widened Farid Semeka Road that has had its garden razed to make way for additional lanes soon leads to one of the five new flyover bridges of Heliopolis. The bridge hangs above the now twelve-lane 60 km/hour El-Hegaz Street which used to host tram stops that were left to decay before disappearing without a trace. A café sits under the bridge where pupils from the schools on this main thoroughfare attempt to cross the road and workers wait for their buses at an unmarked bus stop. This confluence of sudden urban transformation still carries the name El-Hegaz Square although there are no signs to be found that a square ever existed at this site. Further down the road, school pupils attending The English School attempt to cross the widened Abu Bakr El-Siddiq Road with the help of a traffic warden in high-vis gear. He resorts to hand gestures as a signal to vehicles driving on what is essentially a highway to slow down upon their descent from yet another flyover bridge so that he may chaperone the school pupils and other pedestrians across. They quickly walk over neat asphalt that sits atop what once was tramway tracks and greenery. The vehicles that reluctantly came to a stop will soon face more flyover bridges further along this same road, including two that intersect in a fantastical sight, creating a multi-tiered road network that leads to the Almaza neighbourhood whose residents have been facing evictions.

ورجعت وحدى فى دنيتى حاسة بغربة فى نظرتي

مع اننا كنا هنا فى الحى ده مع صَحبتي

فين الصُحاب فين الجيران متغربين لية فى المكان؟

Alone, I returned to my own world

With a sense of estrangement in my gaze

Even though I was just here in this neighbourhood with my friend

Where are the friends? Where are the neighbours? Why are they estranged in this place?

- We Lived Here (In the Past), Hanan

Why are we estranged in this place? How do we navigate the fragmentation and feelings of estrangement in the aftermath of such radical change to infrastructure that created enclaves in a district once famed for being self-contained and well-connected? How do we make sense of the definitive sight of these times: the bulldozer standing victorious next to uprooted trees? It is estimated that 2,500 trees were uprooted between 2019 and 2020 in Heliopolis alone[1]. How do we process the sight of uprooted trees that lie criss-crossed on main roads, once the sight of multiple forms of socio-spatial interaction? The questions we ask bring to the fore further questions, but they also bring with them individual and collective practices to counter the estrangement and the disembodiment. How do these practices that arise in this moment enable us to think through questions pertaining to collective memory in relation to space, and the broader battle over memory in the face of the disappearance of the familiar that shapes our sense of identity? How may we archive the city without lending our archives to narratives that seek to romanticise a city that once was while ignoring how it has been experienced by the subaltern? In a context such as Heliopolis’ that is shaped by a specific colonial history, how can our archival practices also prompt engagement with that past as we make sense of fragments from our present? In our documentation of urban decay in particular, what draws us to it, and what futures do we seek for it in a context of neoliberal urbanisation?

لفو بينا قالو لينا على المدينة

لما جينا التقينا

كل شىء فيها ناسينا

They put us in a whirlwind

They told us to head to the city

When we got there and met each other,

We found that all parts of it have forgotten us.

- The City, Mohamed Mounir

I have been asking myself these questions since witnessing the urban transformation that my home district of Heliopolis, Cairo has undergone since 2019. My response to this has been characterised by panic, fear and a sense of urgency to document as much of the familiar mundane and everyday encounters as I can while they persist in a context that risks their obliteration. This reaction has also included a need to document destruction in progress, perhaps as a means of immortalising scenes that have brought on these affects and as a form of memory work. The documentation I do is primarily through photography that rarely considers aesthetics but is more interested in acting as an archival practice. To date, I have amassed around 2,000 primary photos of Heliopolis and have created an Instagram account, Archiving Heliopolis (@archivingheliopolis), to publicly share some of these photos I have been compulsively taking as a means of managing anxieties around erasure and navigating feelings of disembodiment. A growing number of similar accounts on social media concerned with archiving different aspects of the city in Egypt highlight a particularly precarious temporality that is being navigated against a backdrop of disappearance and erasure. The photos are arguably “a defense against anxiety”[2]. Meaning is seemingly being assembled through “ruins, excavations, and rag-picking”[3] with the aid of a camera. This archiving is continuously creating a wealth of visual repositories that can be referred to in attempts to reimagine the city and counter fragmentation. While the digital nature of these archives simultaneously creates further precarity through the ease by which they can be deleted[4], encounters with them compel us to engage with questions around the convergence of memory, archives, photography and affect, enabling us to better understand how erasure as blackout is navigated, and how meaning is sustained and continuously created individually and collectively.

Notes

[1] Menna A Farouk «FEATURE-Egypt's street trees fall foul of urban development drive, » Thomas Reuters Foundation May 20, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/article/egypt-environment-trees-idAFL5N2X82GR

[2] Susan Sontag. On Photography (New York: Farrar, Rosetta Books, 1973), 5.

[3] Mayada Madbouly and Aya Nassar, “Fragment(s) of Memor(Ies): The Enduring Question of Space and Storytelling.” Egypte/Monde Arabe, no. 23 (December 2, 2021): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.4000/ema.14734.

[4] Hatem, Reem et al. “Instagram Lives.” Filmed June 2022 at CILAS, Cairo (as part of the hybrid conference Virtual Otherwise). Video. Private URL provided to author through private Instagram communication.

Bio

Amira Elwakil is an Egyptian participatory educator, independent researcher and curator of @archivingheliopolis on Instagram through which she documents the district of Heliopolis, Cairo primarily through using photography. She holds an MA in Gender Studies and is interested in observations on the urban condition, including in London where she currently lives.

Glass and Glare: Reflections on Balcony Glazing in Beirut

A Photoessay By Aya Nadera Zantout and Meriam Soltan

As light travels through the atmosphere, it collides with the occasional surface and scatters. In cities like Beirut, that surface is likely to be a glazed panel of some sort. While most light, whether emitted by the sun or projected from a lamp, manages to pass through the glass in question, a sizable portion will be reflected upon impact. Although standard glass is translucent in principle, it often assumes the properties of a mirror. In it, the conditions of the city are reflected and refracted across Beirut, ad infinitum.

Once confined to the space of the window or sliding door, these urban echoes now sprawl across the glazed expanses of the city’s many balconies. The panels of curtain glass that run their perimeters ricochet instances of street life skyward and replicate the mess of frayed wiring and faulty infrastructure suspended in the air between them. And though they double and triple the affairs organized across Beirut’s many apartments and alleyways, these palimpsests of mirror images go largely unnoticed by the people that populate them.

The existence of these reflections at the edge of our perception helped qualify the practice of balcony glazing for legalization in 2004. While balconies are typically classified as outdoor spaces, the amendment introduced to Beirut’s 1983 Construction Law stipulates the right to their enclosure should the material used to do so be of a transparent nature. More specifically, enclosing materials must be adjustable and affixed to tracks—akin to the traditional curtains they have largely since supplanted[1]. The amendment was promptly adapted into both new and old construction schemes across the city. It added sorely needed living space to older apartments and maximized allowable footprints—and thus profits—for contractors building anew. Any ragged fabric seen whipping in the wind today is arguably more indicative of class difference than it is of preference. To register which of these spaces still maintain a relationship with the elements—with the sun, the wind, and the stars—is also, in many ways, to trace financial insecurity apartment by apartment, neighborhood by neighborhood, across the city.

Due to the severity of the infrastructural collapse in Beirut, balcony glazing affords an illusory measure of safety and control to those attempting to brave these conditions. It staves off what it can of waste-crisis born pollutants while keeping at bay the thick haze of smog that now perpetually blankets the city. With dwellers turning collectively in and away from the noxious effects of state sanctioned corruption, balcony glazing is now an impulsive, standard practice for those who can afford it. Each panel installed envelops the transitional area that is the balcony and firmly distinguishes the space of the city from that of the dwelling. And that is not without consequence.

Embraced though it is as non-material, balcony glazing has tangibly transformed the very fabric of Beirut just as it has altered our own relationships to it. Terraces once open to sea, sky, street, and neighbor are instead sealed off with panes endemic to the very crises they are meant to moderate. The same debilitating cycles of extraction and consumption razing the country are only further fortified here to provide the resources necessary for the accommodation of this practice. The sheer quantity of extraneous material balcony glazing has introduced into the cityscape since 2004 has made glass one of the country’s leading imports,[2] and balcony glazing one of its most lucrative, privately funded sources of infrastructural support. It is also one of the deadliest.

Invisible and yet ever-present, glass introduced by way of balcony glazing would continue to accumulate across Beirut only to shatter in the port explosion of August 4, 2020. The resultant shards claimed the lives of over 200 people and maimed thousands more. Equating glass’ transparency with immateriality proved lethal. With the reasons for its initial installation—like pollution and poor air quality—only further exacerbated by the blast, much of these panels have since been restored or replaced. These cycles of repair and ruin position balcony glazing as both a product and purveyor of Beirut’s relentless collapse.[3] This practice makes legible the consequences of social, economic, and political turmoil as embodied by the built environment, and it contributes to the compounding of these crises through the consumption of material it warrants. Every sheet of curtain glass installed is material mined, extracted, and imported.

Even though the requisite resources are fired and finished to near invisibility, the consequences of their making are plainly reflected across the city in a perpetual collision of light and political crisis made manifest. Rarely is this urban spectacle cause for conversation, but that is not to say that its sensorial implications on our shared experience of the city are not deeply felt and sorely recognized. Regardless of how accustomed we are to all manner of calamity in Beirut, each intervention on the built environment unsettles and recalibrates our relationship to it. Balcony glazing, while inconspicuous and understated, is symptomatic of a shared incapacity to withstand the adaptation demanded of us by the failed infrastructures and services that litter the city. For amongst the panes that mirror reality back to us, the occasional burst of glare will inevitably overwhelm the senses, and our eyes, minds, and bodies will simply refuse to adjust.

Artist’s Statement

Like everything else in Beirut, the arts have been severely impacted by the State's collapse. Film is scarce and when one can find it, it is often unaffordable. Developing photography presents its own set of issues too and inconsistencies arise because of it. Shot on Kodak 400 and Kodak Portra 400 35mm film, these images deliberately reflect the collapse in both process and outcome.

Notes

[1] Lebanon, Parliament, Amending Legislative Decree No. 148 of 9/16/1983 (Building Law), Law No. 646, December 11, 2004, Article 14, Section 2, Item No. 1.

[2] “Lebanon Product Imports.” Lebanon Product Imports 2020 | WITS Data. https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/LBN/Year/2020/TradeFlow/Import/Partner/WLD/Product/all-groups.

[3] Batoul Faour, “Glass Politics: On Broken Windows in Beirut,” The Avery Review, Issue 52 (April 2021): https://averyreview.com/issues/52/glass-politics.

Bio

Aya Nadera Zantout is an architect and multidisciplinary artist based in Beirut. Since graduating with a BArch from The American University of Beirut in 2020, she has dedicated much of her creative and professional work to navigating the many intersections of art and the built environment. She often finds herself documenting her city’s conflicting identities as they continue to evolve throughout various crises. Most recently, she has been developing her printmaking practice at Beirut Printmaking Studio, and has participated in collective printmaking shows in Beirut, Liverpool, and Paris.

Meriam Soltan is a writer and researcher interested in the intersections of language, design, and worldbuilding. An assistant editor at Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, she works to explore the design of fictions and how they are manifested in various contexts politically, culturally, and otherwise. Meriam received her Master of Science in Architecture Studies from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2022 and her Bachelor of Architecture from The American University of Beirut in 2019. She is a recipient of the MIT Architecture Thesis Award and the Berkeley Essay Prize, and her writing has been featured in Postmedieval, The Funambulist, Rusted Radishes: Beirut Literary and Art Journal, MIT’s Thresholds, and ETH Zurich’s Trans Magazin.

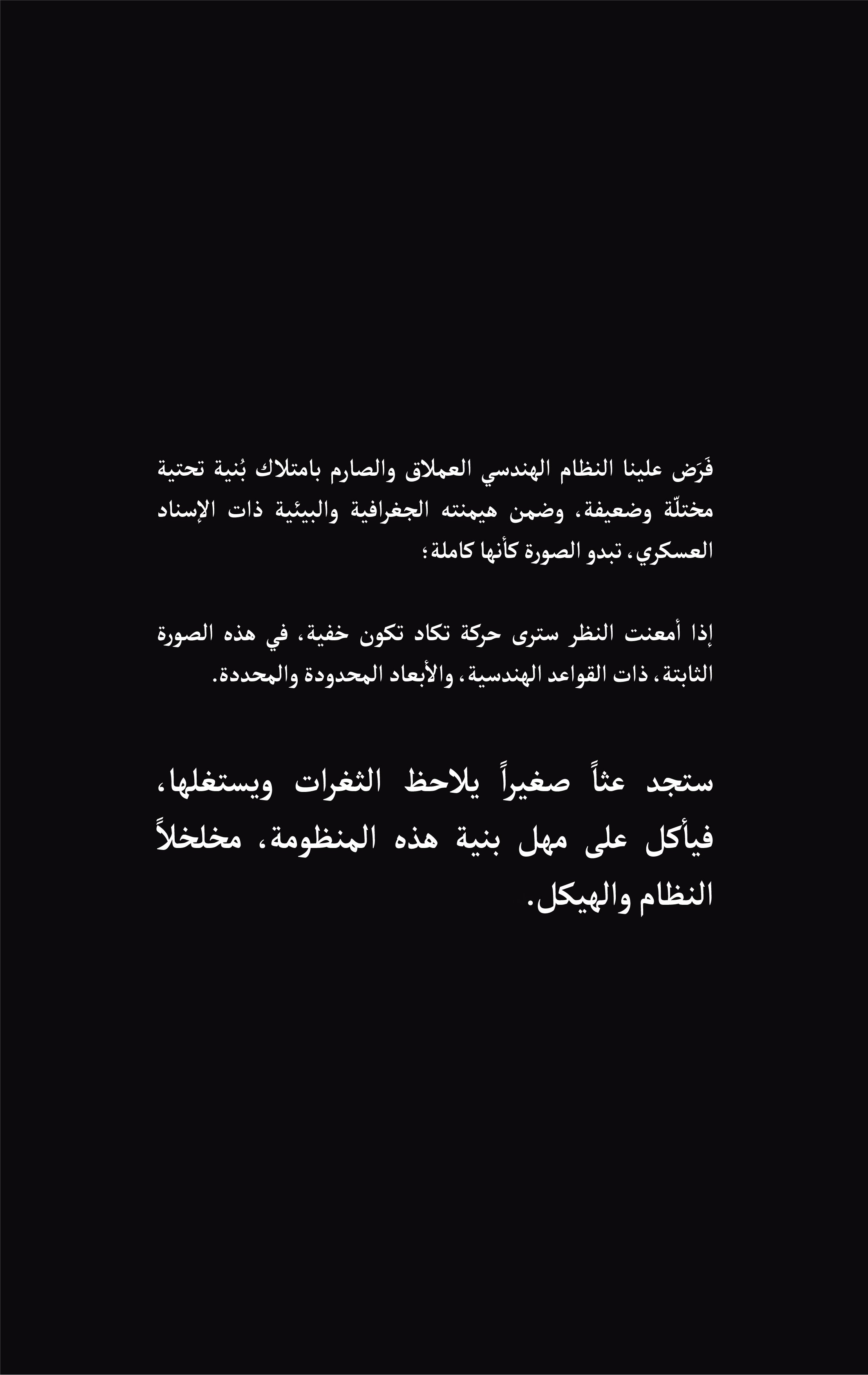

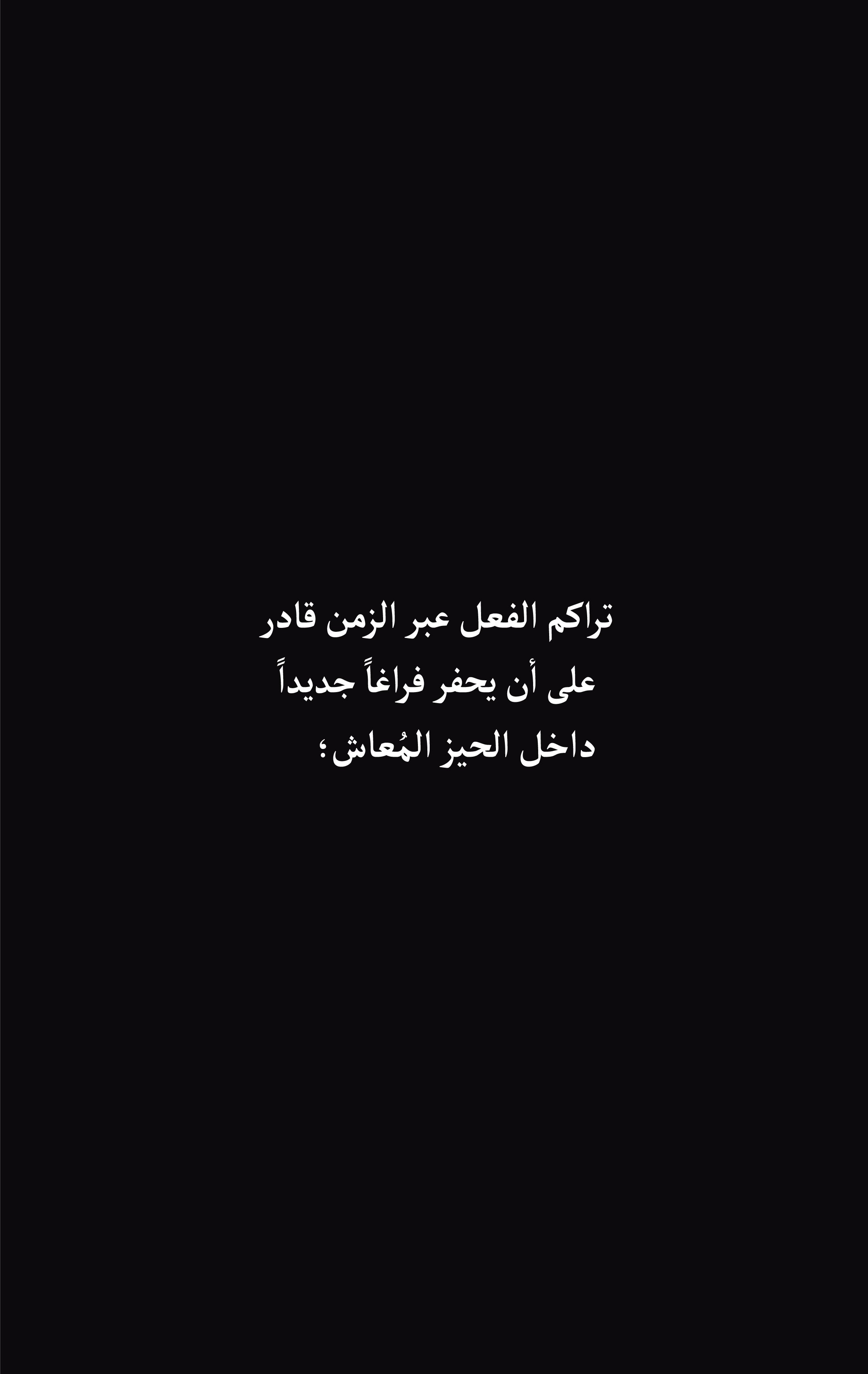

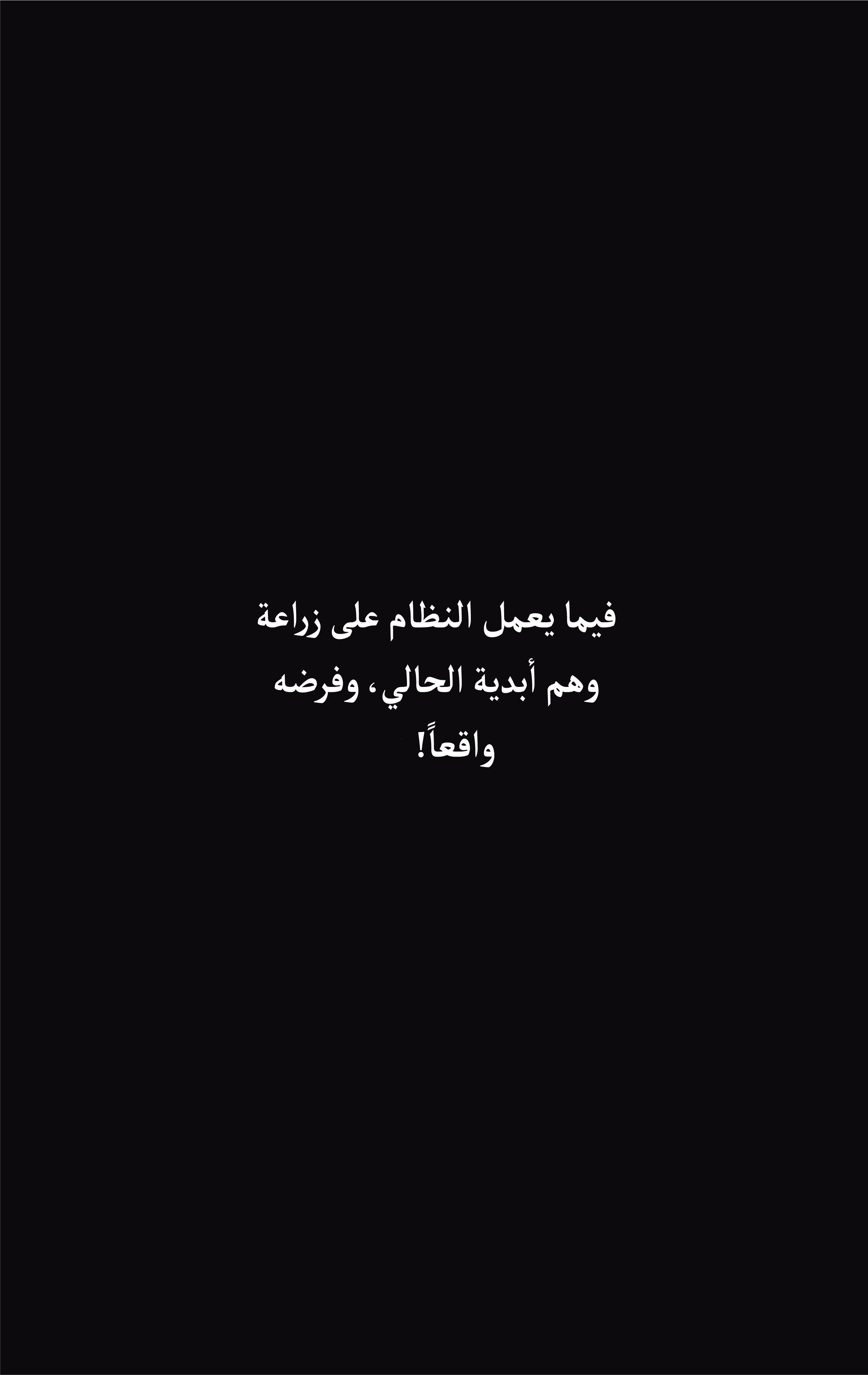

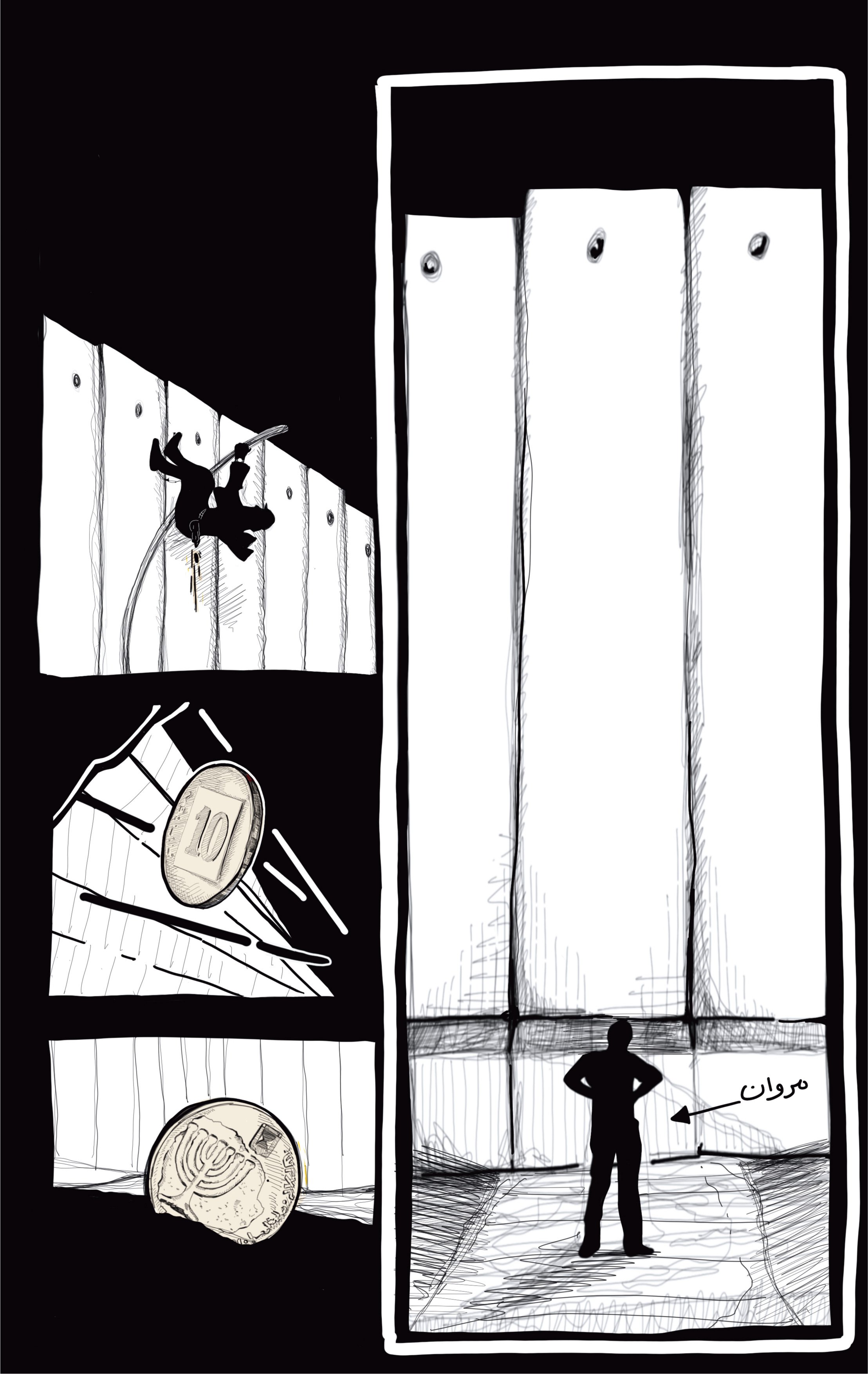

ملاحظات من وادي العين

جورج تادرس وترتيل مُعمر

السيرة الذاتيّة

جورج تادرس، مهندس معماري يعمل في مجال العمارة والبحث والتصميم، حاصل على درجة البكالوريوس في الهندسة المعمارية من جامعة بيرزيت، ويعمل حالياً كمساعد بحث وتدريس في كلية الفنون والموسيقى والتصميم في جامعة بيرزيت، إلى جانب عمله كمهندس مبتدئ في شركة معمارية في القدس. مهتم في دراسة دور التدخلات الهندسية محدودة النطاق، كآليات تحوّل في الحكم الحضري في فلسطين.

ترتيل معمر، منسقة مشاريع تعمل في مجال الثقافة والفنون، حاصلة على درجة البكالوريوس في الصحافة والعلوم السياسية من جامعة بيرزيت، مهتمة بالإنتاج السينمائي، والثقافة البصرية بوسائطها الفنية المختلفة.

أعمال ذات صلة

Climate Vulnerability and Slow Violence in Kuwait

A Photoessay By Geoffrey Martin and Mariam AlSaad

Image 1: A lonely lifeless tree in a public park, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Kuwait is an arid country with few natural resources. Only 0.6% of Kuwait’s land is arable, the remainder is largely an asphalt-like rubble strewn desert, contaminated by oil and soot from wars and industrial pollution. The country is heavily impacted by climate change with average temperatures increasing over the last few decades and higher instances of extreme weather events like heavy dust and rainstorms. Kuwait also has one of the highest CO2 per capita emissions globally.[1] The increased land surface temperatures come with an increase in energy consumption and carbon emissions due to the rising demand for indoor cooling, creating a vicious cycle that amplifies climate change impact. Kuwait’s disjointed and ineffective political system also hinders the development of infrastructure, policies, and regulations to guard the country from ecological crisis. This climate-changed geography has harmed human health and well-being while resulting in the deterioration of infrastructures and urban landscapes.

These slowly unfolding urban and environmental crises which consist of extreme heat, air pollution, waste accumulation, and infrastructural degradation are particularly experienced by marginalised communities who have uneven access to safe, effective, and resilient infrastructure and services. Making up a little over 70% of the total population, migrant workers in the service industry, oil, construction, and industrial sectors are considered to be one of the most vulnerable groups in Kuwait. With a majority of whom are South Asian, coming from lower socio-economic backgrounds and doing physically demanding jobs, these workers often live and labour in areas which are subjected to forms of slow violence. They lack equal access to essential facilities and services such as healthcare, transportation, and legal systems, and are subjected to state-sanctioned discrimination and xenophobia.

Rob Nixon defines slow violence as a form of violence which “occurs gradually and out of sight”, and sometimes it is “not viewed as violence at all”. Environmental degradation, such as massing greenhouse gasses, accelerated loss of species due to plundered habitats, and toxic build-ups, can be seen as a key outcome of slow violence. Nixon also states that slow violence “impacts the environments -and the environmentalism- of the poor” and is highly intertwined with different forms of inequality and structural violence.[2]

The photographs of deteriorating infrastructure and environmental degradation in this essay are mainly captured in areas such as Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh, Mangaf, and Salmiya, which are predominantly populated by non-citizen workers. They expose the realities of marginalisation, classism, dependency, and exploitation. They document infrastructural failures in the form of severely damaged roads that result from flooding, unmaintained poor urban spaces, decaying surrounding environment, improper housing units, unsanitary waste accumulation, unsafe walking paths, and limited access to public transportation. The testimonies given provide a vivid unblemished expression of the urban experience of migrant workers in Kuwait. Their stories are often unheard and overlooked even though they are at the center of multiple social, economic, environmental crises and the main victims of slow violence.

Image 2: A view from a beach of polluted waters with a tanker traversing the Arab Gulf in the background, Fintas

Image 3: Food and other refuse in a public park in Salmiya neighbourhood, Salmiya

Image 4: Labourers keeping out of the heat behind a barbed wire barricade, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

This visual essay illustrates migrants’ experiences of slow violence while accounting for the deterioration of Kuwait's infrastructure and ecosystems, and how the status and vulnerability of these migrant workers make them victims of a bleak, escapable dystopian reality.

These experiences highlight the challenges and tribulations that these victims face daily in silence, distant from the rest of society. Due to the relative invisibility of the slow violence, we felt it is incredibly important to amplify the voices of those affected, and to share their stories through this medium of visuals and testimonies. To capture struggle and deprivation through a lens would be difficult, but the setting of urban decay and anarchy in Kuwait allowed us to provide a glimpse into how slow violence grinds down vulnerable populations.

Testimonies

Image 5: Trying to stay cool while shopping, Friday Market, Alrai

Testimony A

“Going outside is like landing on a different planet. The harsh conditions, toxic climate, increasingly beating wind. It’s like being on Mars. When I see the city, it reminds me of crumbling stale bread or rotting meat. It feels like the whole place is grinding against you, pounding, pushing, and squeezing you towards its demise and your own demise. Sometimes I feel like I’m in a bubble that is ready to pop.” - J, Ugandan, 35, Delivery Driver, Male

Time in Kuwait: 4 years

Motorcycle delivery drivers in Kuwait often drive for hours, with few legal protections from employers who push them to work in extreme weather conditions such as high temperatures and storm events. Drivers must often wear heavy clothing to avoid serious skin damage, and often consume nothing but water during 15-hour shifts. Damage to their physical and mental health is significant, and there is little recourse for treatment or a different lifestyle. While the salary is much better than other menial jobs, it comes at a high health cost.

Image 6: Taking cover in the heat downtown, Alasimah

Image 7: Walking home from work in 51C, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Testimony B

“I always feel as if looking is violence against my eyes. I squint to avoid dust and pollution in the air, but also simply because my mind doesn’t like what it see. I hide like a rat to get away from this, always inside. It’s like living in a city during a nuclear winter”. - R, Filipino, 28, Salon Worker, Female

Time in Kuwait: 3 Years

Migrant workers often live in areas that are in close proximity to industrial zones where toxins and pollutants are potentially seeping into the air causing pollution and discomfort. There are virtually no environmental regulations or oversight over these migrant housing areas, such as Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh or Mahboula, which have illegally built-up poorly constructed tenements and makeshift “chincos” (small corrugated steel sheet dwellings). More often than not, migrants live on their work sites to avoid paying rents they can ill afford.

Image 8: Open air market, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 9: Slum housing, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 10: Driver’s section of a burnt out bus, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 11: Dying palm tree, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 12: Passenger’s section of a burnt out bus, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 13: Slum Alleyway, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 14: Abandoned building, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Testimony C

“There is a contradiction between the wealth that the place provides and the death that it creates. Everything feels like an old haunted movie. Sometimes I feel like I can't breathe with the way the whole place is, and then I realize that I actually can't breathe and that the nightmare is real.” - A, Nepali, 43, Safety Technician, Male

Time in Kuwait: 18 years

There is a disturbing relationship between wealth and exploitation. The constant demand for labour and the comforts provided from the fruits of this labour comes at an inhumane cost. While wealthy citizens and residents live in hermetically sealed homes and apartments, just meters away are those who have none of these amenities and comforts.

Testimony D

“No air, feels like living in space.” - M, Filipino, 25, Maid/Nanny, Female

Time in Kuwait: 6 years

Image 15: Discarded license plate, Sharq

Image 16: Kidney donation sign. It is illegal to advertise for organ donations, although it is very common in Kuwait, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 17: Graffiti and chair art. Despite many migrant areas being neglected, there are attempts to beautify the area by residents, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 18: One of countless broken windows in neglected areas, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 19: Abandoned television on the side of a street, Salmiya

Kuwait has very high rates of air pollution. Respiratory illnesses and asthma are endemic to the country’s population. Migrant workers usually live in cramped, poorly ventilated conditions. For the tens of thousands of illegal migrants suffering from health conditions, there is no access to healthcare for the toxin and sand filled air they breathe.

Testimony E

“Back home the rain brings good things, but in Kuwait it feels like a harbinger of death. The water has nowhere to grow and nothing to feed. No love and no life, a heartless place. The water seems and feels out of place, useless with no real purpose other than to damage the badly made streets and buildings. It almost feels like a punishment more than a blessing.” - R, Sri Lanka, 44, Translator, Female

Time in Kuwait: 17 years

In areas where infrastructure is under-developed and under maintained, flooding is a common occurrence in the winter months. In the aftermath of rainstorms, broken sidewalks and shattered pavement are the most common sight on Kuwaiti roads. Millions of sandbags, used to build flood walls, litter the main thoroughfares, backstreets and sides of buildings as if part of a failed defense against a relentless invader.

Image 20: Mid-day stroll in 52C, Mangaf

Image 21: Sewage filled streets, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Testimony F

“In the summer I enter a particular type of hell. In the factory the air conditioner and ventilation doesn’t work properly.” - P, Indian, 34, Factory Worker, Male

Time in Kuwait: 5 years

Migrants who work in industrial areas often labour in substandard work environments. Labour laws in Kuwait notoriously disadvantage migrant workers from claiming their most basic rights, including changing jobs, driving a vehicle, or living with their families. These policies force them to live and work in places that reduce their quality of life.

Image 22: Workers accommodation, Al Rai

Testimony G

“No bird, no insects, no worms, no life.”- H, Ghana, 34, Warehouse Worker, Male

Time in Kuwait: 2 years

Ecosystems in Kuwait have been heavily damaged by climate change while the local population has been deprived of the ability or right to interact with nature. A healthy ecosystem is a thing of the past. Native flora and fauna are often only identifiable through school textbooks, museums, and collective memory.

Image 23: Dead tree, Sharq

Testimony H

“There is disrespect and racism by nationals. Politics in Kuwait are oppressive with disdain for foreigners or difference. For us there are no rights, no freedoms. It feels like even the weather is against us now.” – A, Egypt, 44, Clerk, Male

Time in Kuwait: 30 years

Increasing racism against foreigners, but particularly against migrant workers from Egypt and Southeast Asia, has made living in such a harsh environment more challenging. The climate crisis is compounded by socio-political crisis.

Image 24: Shopping in Friday Market, a primary destination for low-income migrant workers, Alrai

Testimony I

“I desperately need to be in Kuwait to support my family, but I just can’t take it anymore. I am out on the road for 12 hours a day, driving around waiting for deliveries. The sun in July was so bad that I was getting sunburned even through the tiniest crack in my clothes or helmet visor.” - G, Indian, 31, Delivery Driver, Male

Time in Kuwait: 6 years

Most migrant workers come to Kuwait to make and send money to families back in their countries of origin. Families often sell homes and other valuable belongings to facilitate migration to Kuwait. The currency exchange rate of the Kuwaiti dinar makes for a tempting offer for those coming from countries with more precarious economies. Yet many realize too late that the money is not worth the cost to their health and wellbeing.

Image 25: Waiting for a customer at an autoshop, Salmiya

Image 26: Shopping in the heat, Friday Market, Alrai

Image 27: Waiting for a customer in 51C, Friday Market, Alrai

Testimony J

“The clinic fills up with people during the hot months complaining of headaches, shortness of breath, and aches and pains. People are looking for a cause to these pains when it's simply the weather outside. It’s unbearable.” - E, Filipino, 31, Nurse, Female

Time in Kuwait: 3 years

Migrants’ health burdens due to climate crisis and economic precarity are exacerbated by a healthcare system without the capacity to handle the current patient load. Most migrant workers are turned away and advised to procure painkillers, cough syrup and other drugs over the counter to self-medicate. This not only fails to address the problem, it often reproduces healthcare burdens overtime.

Image 28: Working on a villa roof in 50C. Construction labourers rarely wear protective equipment while working in dangerous conditions and extreme temperatures. Workplace accidents are frequent, Salmiya

Image 29: Workers labouring in 50C heat to install parking shades, Hawalli

Image 30: Friday Market offers a diverse urban shopping experience, despite poor public transportation access and a lack of amenities to deal with increasing temperatures, Alrai

Testimony K

“Millions of birds come to Kuwait each year. They struggle, drinking water from stagnant pools surrounded by broken concrete and chipped bricks. They stagger around, like they are drunk. Date palms and mangrove struggle to hang on to life and oil, withering in groups, most often defeated after a long battle with thirst. I watch them die and wonder if I am next.” - RJ, Indian, 48, Engineer, Male

Time in Kuwait: 6 years

The degradation of the environment has impacted the few species that live and migrate to Kuwait in ways that will not only impact the Gulf, but also the wider region. Without migration sanctuaries to support transcontinental flights, birds are trapped in Kuwait, much like the undocumented migrants.

Image 31: Malnourished dog hiding from the heat. The carcasses of dead animals, birds, and other insects are a common sight during the summer months, Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh

Image 32: Derelict boat in an abandoned garden, Salmiya

Image 33: Waiting for the bus in 50C, Hawalli

Image 34: Pondering life, Alrai

The climate crisis will cast a shadow over Kuwait’s man-made urban mayhem, ecological and infrastructural degradation, and its complex sociopolitical scene. Its most vulnerable communities are victims of slow violence that affects their housing, transportation, development, health, and quality of life. If no policies and structural changes are made to rectify the current situation, this violence will continue to create unhealthy urban spaces and harm the lives of many.

Notes

[1] “CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita) - Kuwait”, The World Bank, accessed April 26, 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC?locations=KW.

[2] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press, 2011), 2-44.

Bios

Geoffrey Martin is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Toronto, entrepreneur and economic analyst in Kuwait. His focus is on political economy, food logistics, and labor law in Kuwait and the wider GCC. He is the founder of Kuwait Aid Network, a non-profit that focuses on supporting migrant workers in Kuwait. He tweets @bartybartin.

Mariam AlSaad is a LEED-certified Civil and Structural Engineer at the Design Department of the Kuwaiti Ministry of Public Works. Mariam has a Master of Science in Sustainable Cities. She does research on sustainability in the built environment, climate and social issues, and the relationship between urban design and people. She is the founder of AlManakh, a non-profit that aims to raise awareness regarding climate change impacts and sustainability in Kuwait. She tweets @mariam__alsaad.

Remaining Cairo: Bridges, Fragments, and the Persistence of Memory

A Poem by Zain Farhan

A series of poems by Zein Farhan

June 2023

Bridge /brij/ (noun/verb)

To bridge is to reconcile, to connect. To fragment, to dismember, to uproot, to displace. Thick, impermeable concrete settles in the veins of the city. To keep us in motion, supposedly. One body discarded, to eternalize a future. Remember where we lived, walked, played, and buried our dead? Flyovers atop cemeteries, ancestors crushed under steel and stone. Uprooted trees line the road to modernity. One city cleansed, to ensure impermanence. We negotiated space, a desire for memory. Victorious, she emerges, despite.

To bridge is to reconcile, to connect. To fragment, to dismember, to uproot, to displace. Thick, impermeable concrete settles in the veins of the city. To keep us in motion, supposedly. One body discarded, to eternalize a future. Remember where we lived, walked, played, and buried our dead? Flyovers atop cemeteries, ancestors crushed under steel and stone. Uprooted trees line the road to modernity. One city cleansed, to ensure impermanence. We negotiated space, a desire for memory. Victorious she emerges, despite.

Bridge body buried

A future dead steel stone space

For victorious

For Remembrance

What was disjointed

What was stolen

What was obscured

What was erased

What was here before

What is here, still?

What did we negotiate

What survived

What remains

What are the traces

What can we remember

What can we contain

What can we condemn

What can we forgive

What can we transgress

What is theirs

What is ours

What is beyond

Cairo Reborn

Raze ancient trees. Twelve-lanes across the Nile, congratulations on the world’s widest suspension bridge. After erasing El Warraq, Horus City ablaze with commercial and residential buzz. King Salman peering through the window, its axis 50 centimeters away from homes. Bulldoze burial sites. The living in the City of the Dead rising, relocated to 6th of October. Bulldoze more burial sites. The only heritage is dazzling, a new Cairo is coming. Maspero, developing the heart of the capital. Bulldoze more burial sites. Even the dead cannot rest. Another satellite city. Iconic Tower. A crystal pyramid. The Octagon. A new center of gravity. The global city emerges, modern.

Note

In recent years, Cairo has been subject to the construction of a mass of bridges, with over forty planned in total. While the rationale for constructing bridges and highways is to alleviate traffic congestion, bridges are incomprehensibly fragmenting the urban landscape. These spatial ruptures, similar to much other transportation infrastructure that is positioned as the resolution to decades of poor planning, are causing displacement, environmental degradation, and the destruction of cultural heritage sites. Remaining Cairo: Bridges, Fragments, and the Persistence of Memory is a series of poems that explore this fragmentation of the urban landscape in the context of erasure of public memory and knowledge, and the uprooting of human and more-than-human entities to make way for permanent and impermeable concrete. The poetic forms that relate to the violence of these infrastructure projects, including a burning haibun.

Bio

Zein Farhan (Pseudonym) is an Egyptian artist-researcher exploring the ever-changing politics of space, and trying to remember. They enjoy swimming in the sea and playing with light.

Electricité du Liban: A Vertical Mazra'a

A Photoessay By Iyad Abou Gaida

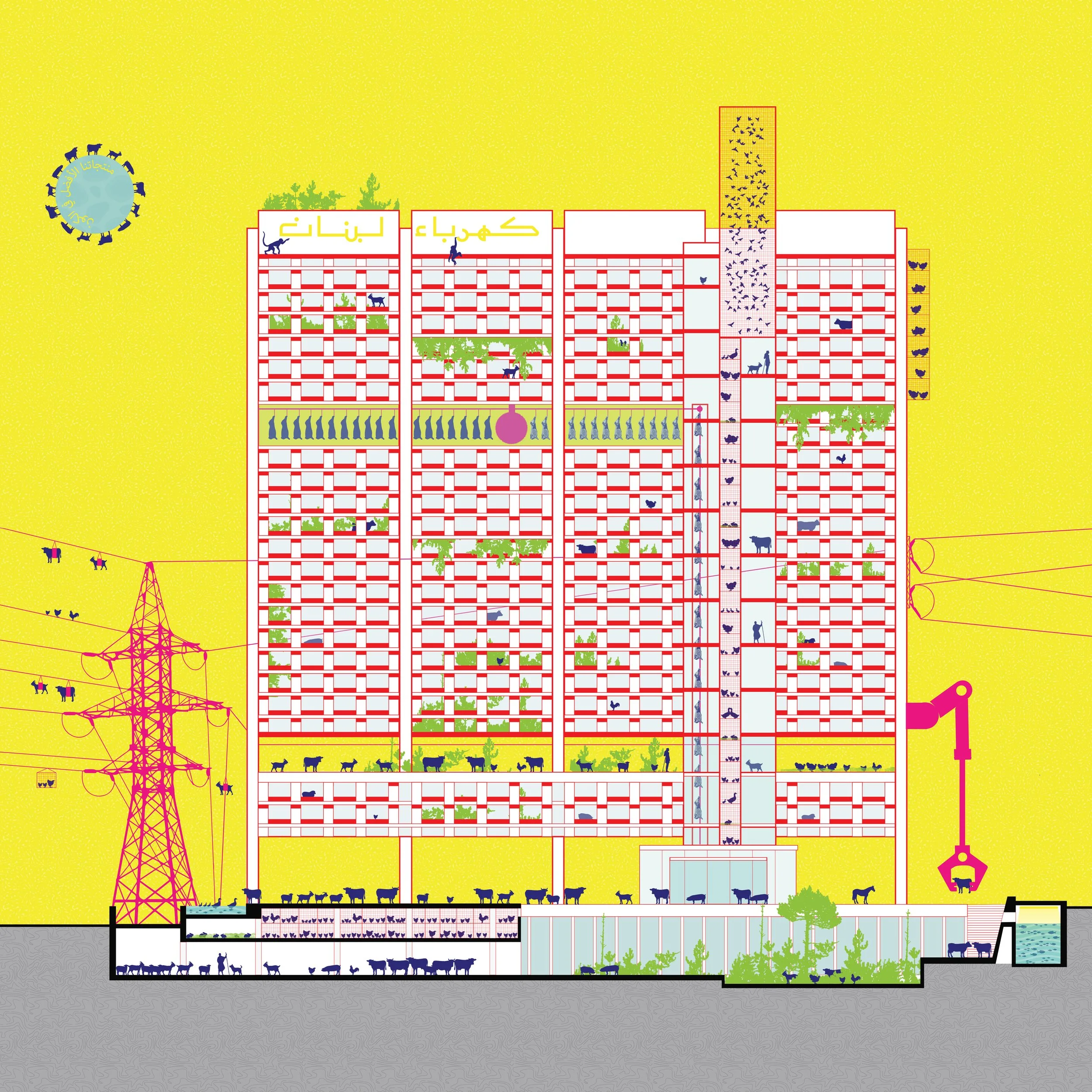

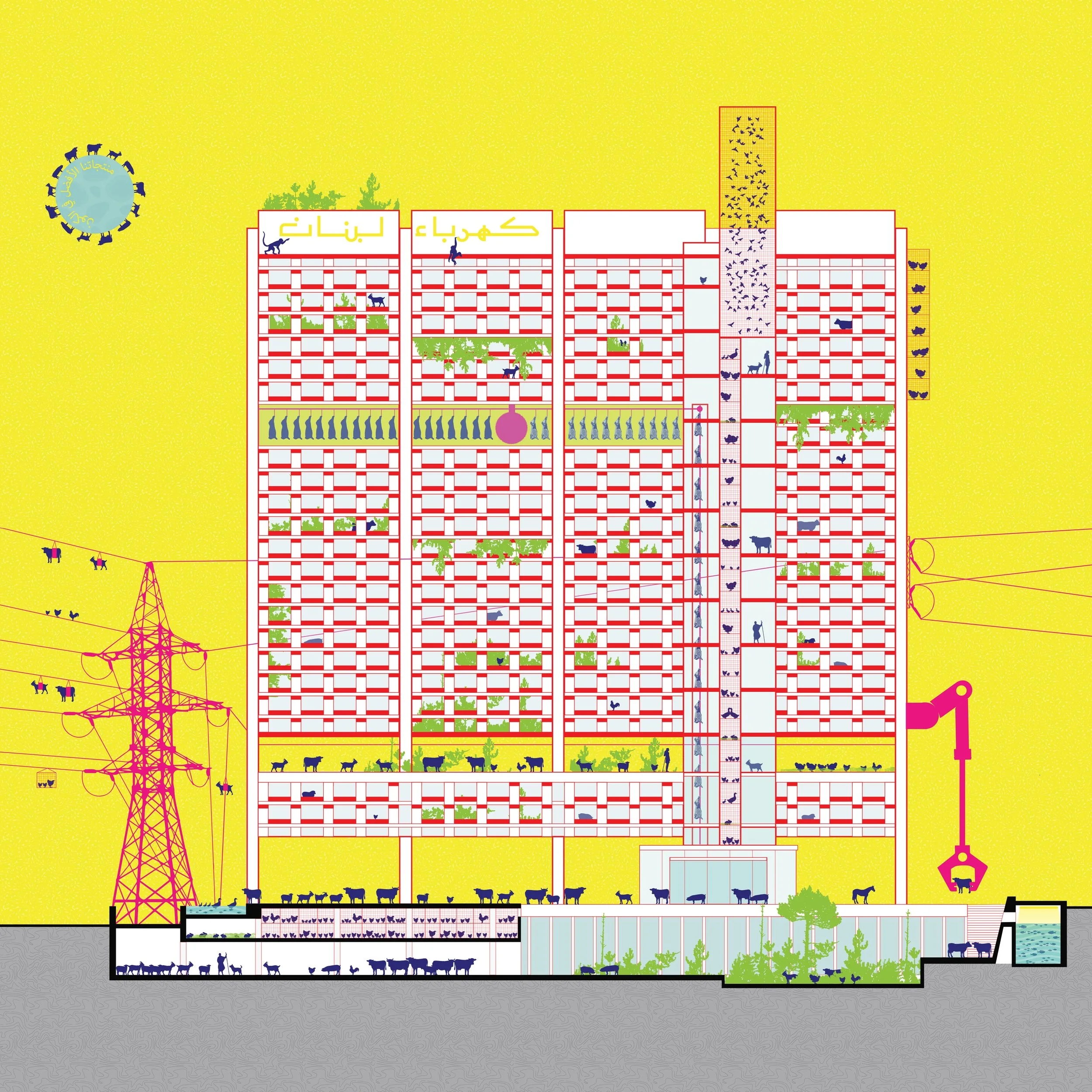

Figure 1. EDL Vertical Mazraa' is a cynical illustration that re-imagines the state-owned EDL (Electricity of Lebanon) Headquarters as an Urban Vertical farm controlled by competing entities.

In August 2018, the Lebanese woke up to several media outbreaks reporting the existence of a makeshift chicken coop at the state-owned electricity headquarters - Electricité du Liban (EDL). The coop, made of wooden cages and electric incubators, hosted an array of avian species such as chicken and quail. The claims made by the media were later confirmed by EDL's spokesperson and the Ministry of Energy and Water. The chicken coop generated another fleeting public outcry on the streets of Beirut[1]. What caused outrage was the fact that the coop was supplied with 24/7 electricity when the city of Beirut was being subjected that summer to blackouts of more than 10 hours a day. This controversy and the modern ruins that the EDL represent speak to the failures of the colonial and postcolonial project of modernisation in the Levant.

Power cuts have long been a part of life in Lebanon. The dysfunctional electricity sector is a product of the legacies of the French colonial project, government corruption, and foreign intervention. After Lebanon’s independence in 1943, Beirut seemed to be a prospering metropolis, at least to the wealthy and bourgeoisie in the city. The 1950s and 1960s were times where the newly independent nation-state focused on situating itself as a major regional player. Embracing the promise of modern infrastructures, the elite political class hoped to build a modern country based on the blueprint left by the French colonial empire. This period witnessed a surge in architectural development embedded in modernist ideology introduced by young Lebanese architects that had recently graduated from European universities, mainly from France. The government especially under Fouad Chehab presidency mobilized these young architects to establish a new national identity, a “modernist” ethos, that had its roots in Europe, and which sought to counter Arab nationalism in the country and efforts to establish modern sovereign states in the region.[2] At that time, France was – and unfortunately still is – considered as the ‘mother country’ by most of the ruling political figures.

The period's modernist optimism is exemplified by EDL headquarters, designed by the architect Pierre Neema and CETA group in 1965. Pierre Neema was one of the prominent French trained modernist architects in Lebanon. After studying in France, and several years of training in various Parisian architecture firms, he decided to return to Lebanon in the 1960s and established the CETA group, a team of Lebanese and French architects and engineers including Jacques Aractingi, Joseph Nassar, and Jean-Noel Conan.[3] In addition to the EDL, Neema and CETA group designed and built emblematic buildings such as the Postal, Telegraph and Telephone (PTT) service building in Bir Hassan, the EDL power station in Furn El Chebbak, and the Maison de L'artisan Libanais.

The EDL was designed to be a modernist edifice. This massive concrete structure hovers above a sunken public courtyard, offering the neighbourhood a nestled urban pocket and a view towards the Mediterranean Sea, a space of generosity where massive institutional buildings seem to welcome the public and convey a sense of transparency. The company’s headquarters assert the ruling government’s aspiration to supply services far into the rural territories of Lebanon. It was intended to be an icon not only to Beiruties but for all citizens throughout the country – a modernist infrastructural building that represented the newly established state of Lebanon as a concrete materialization of a homeland for all its citizens. Today, the EDL’s worn façade, its collapsed service systems, archaic office spaces, and gated sunken courtyard, exemplify the disappointments and failure of modernity in Lebanon. Indeed, the building that was supposed to represent a modern utopian dream tells the story of the aspirations and the failures of the country.

In Lebanon, there is a colloquial word people use to describe governmental institutions: "Mazra’a." Mazra’a means farm in Arabic, however the Lebanese have adopted the term to vaguely express the chaotic state of governmental institutions. The EDL’s headquarters is perceived as a Mazra’a. But why Mazra’a? Some, mainly the urban bourgeoisie, link Mazra’a to the rural, a place that did not embrace modernity and civilization. Others use the word as an analogy for feudalism – a system of hierarchy, where lords have rights over virtually everything and look at their “subjects'' as mere objects stripped of all rights and agency. My great uncle, Mohana Al Safadi, refused to use the word Mazra’a. He always referred to our farm as “ʼArd,” which is the Arabic word for land or earth. He believed ʼArd to be a place of nurture, a generous and giving extension of the ecosystem. In a way, I believe he looked at ʼArd as a complex and diverse territory beyond private ownership, a place cared for by its custodians where foragers, herders, and non-human species can inhabit and move freely. ‘Ard, as in my great uncle’s understanding, recalls a healthy ecosystem with transspecies alliances and relationships that ensures regeneration.

Unlike ʼArd, a place of belonging, the modern Mazra’a departs from the traditional and historic farming practices in the region. The term in Lebanon is used as a synonym to the industrial farm, a foreign concept introduced by modernity with no regards to natural cycles, context, and relationships among living beings – human and non-human. It is a site of monocultures and mass production guided by strict economic structures, where beings are exploited and isolated from their natural habitat, a system that needs continuous intervention in order to maintain short term profit at the cost of longevity and overall health of the ecosystem. Lebanon, like a modern Mazra’a, was designed to be isolated and exploited by the colonial powers and, later, by political and economic elites. Separated from its natural and historic relationships with neighbouring communities, the country has been left with minimal resources, unable to exist without continuous foreign intervention. Just like a factory farm – simply Mazra’a as locals refer to it, the inhabitants of this land are exploited in every possible way to generate gains – economic, political, or otherwise – for few local and foreign players. A century after the inception of Lebanon the Mazra’a mentality has seeped into almost every aspect of Lebanese life, from public services to institutions, turning the country into the Republic of Mazra’a. Like other governmental institutions, the history of EDL is entangled with the history of Lebanon, both “projects” designed as a modern solution to the needs and aspirations of the people of this territory, each doomed to fail at the hand of the other.

Notes

[1] “عامل يربي الدواجن في مقر مؤسسة كهرباء لبنان,” Al Arabiya, accessed April 24, 2023.

[2] Eric Verdeil, Beyrouth et ses urbanistes: une ville en plans (1946-1975), (Beirut: Presses de l'Ifpo, 2010), 81-106. http://books.openedition.org/ifpo/2170.

[3] Georges Joseph Arbid, “PRACTICING MODERNISM IN BEIRUT ARCHITECTURE IN LEBANON, 1946-1970,” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2002), 49.

Bio

Iyad Abou Gaida is a Lebanese architect and researcher. Iyad worked for offices based in Tokyo, Beirut and New York. Iyad’s research engages ecologies of human and non-human beings to address aesthetic and socio-political urgencies for architecture and urbanism across dimensions and geographies. Iyad is a Co-founder of “EcoRove: Shifting territories and the displaced,” a collaborative project that studies living beings in the Critical Zone.

A Visual Essay by Marwa Shykhon